The Cloud Peak Symphony performed a concert Friday. May 6, at the WYO Theater and Saturday, May 7, in the Buffalo High School Auditorium. We performed Haydn's Symphony No. 86, a movement from Telemann's Wassermusik, an arrangement by Tim, and a nice medley of songs from "Cats." It was great!

I am hoping to post a few minutes of the Cummings piece as filmed by my wife's fancy phone. T

Monday, May 9, 2011

Monday, October 18, 2010

Exciting Concert Ahead!!!

Our November 6 &7 concerts in Sheridan and Buffalo will feature a wonderful Sheridan High School student performing Mendelsohnn's Violin Concerto. He is wonderful to work with and the piece is flying out of the instruments. The Cloud Peak Symphony strings will also perform Grieg's Holberg Suite. The orchestra will open with Beethoven's Overture to Fidelio, and close with Bizet's "Farandole." I am beside myself with glee, or whatever TV show you watch ... me ... Big Bang Theory.

Monday, April 19, 2010

Joyous rehearsal had

Sunday was a great rehearsal. Wonderful to have the Buffalo newcomers there, as well as the regular gang! Strings, I have emended Emendation to relieve us the strife of the "black notes" passage. I trimmed measures 57 through 64. It still makes sense, in a hairy-legged sort of way. See you Sunday!

Saturday, April 3, 2010

Lost in a sea of recording -- Movement and Moment

When young I had no choice but to listen to classical, orchestral music via the recordings – in my case, on 8-track tapes from the auto department of a K-mart 120 miles from home.

Wilhelm Furtwangler (d. 1954) was one conductor in the olden days, and Sergiu Celibidache more recently (d. 1996) that heard and felt the flattening effect of recorded orchestral music, and strenuously objected to it. At a first hearing, Furtwangler insisted that the audio technicians had made the recorded piece unrecognizable.

Recorded music helps point the intellect in the direction of how the piece goes, but, it sacrifices the moment that the music produces in terms of space and movement and placement. These very real aspects of music are compacted and delivered in a recycled, mangled cube of sound in much the same way that automobiles are crushed and returned to the smelters – the subtleties of their design and their very purpose for existing is lost to that father of mediocrity – convenience.

For example, how can it be that the back row filled with trombones, trumpets and horns can pronounce a fanfare, and be answered by the strings with no loss of volume or power? This is a trick of the mixing booth or of the synthesizer. In the auditorium, the strings have their own strength and tension, but it is not to the equal volume, and not the same kind of strength that the brass can put forth. We are accustomed to this now, so in real life, after our impression has been mashed together by recording norms, the strings tend to fail us.

We can't really believe that a solo clarinet on stage, situated in the midst of other winds and surrounded by a sea of strings would sound as though the bell of the horn is 18 inches from our face. Celibidache compared this compacting effect to a photograph, and asked, who would prefer to look at a photo album of the Alps for three days rather then spend three days in the mountains?

I tend to congratulate the audiences of the Cloud Peak Symphony for coming to an actual performance that is not as convenient as flipping on a player at home. “Thank you for joining us in this conspiracy to commit music,” I have said in opening remarks.

In the concert hall, the word “movement” is not only a technical term for a division or section of music, but also a word that describes the experience of living the sound.

Wilhelm Furtwangler (d. 1954) was one conductor in the olden days, and Sergiu Celibidache more recently (d. 1996) that heard and felt the flattening effect of recorded orchestral music, and strenuously objected to it. At a first hearing, Furtwangler insisted that the audio technicians had made the recorded piece unrecognizable.

Recorded music helps point the intellect in the direction of how the piece goes, but, it sacrifices the moment that the music produces in terms of space and movement and placement. These very real aspects of music are compacted and delivered in a recycled, mangled cube of sound in much the same way that automobiles are crushed and returned to the smelters – the subtleties of their design and their very purpose for existing is lost to that father of mediocrity – convenience.

For example, how can it be that the back row filled with trombones, trumpets and horns can pronounce a fanfare, and be answered by the strings with no loss of volume or power? This is a trick of the mixing booth or of the synthesizer. In the auditorium, the strings have their own strength and tension, but it is not to the equal volume, and not the same kind of strength that the brass can put forth. We are accustomed to this now, so in real life, after our impression has been mashed together by recording norms, the strings tend to fail us.

We can't really believe that a solo clarinet on stage, situated in the midst of other winds and surrounded by a sea of strings would sound as though the bell of the horn is 18 inches from our face. Celibidache compared this compacting effect to a photograph, and asked, who would prefer to look at a photo album of the Alps for three days rather then spend three days in the mountains?

I tend to congratulate the audiences of the Cloud Peak Symphony for coming to an actual performance that is not as convenient as flipping on a player at home. “Thank you for joining us in this conspiracy to commit music,” I have said in opening remarks.

In the concert hall, the word “movement” is not only a technical term for a division or section of music, but also a word that describes the experience of living the sound.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Written notes on notes I have written

In my concept of my own music I hear a more robust, muscular sonority from the strings. At first rehearsal, I am usually surprised by the shy sound that we produce together at the first read.

I cannot lay blame for this on the players. In other, better music, especially Haydn and Mozart, I most frequently use the term “finesse” to evoke a joyfully measured forte. “Excitement, not anger,” I will say. “In Haydn, ‘f’ means ‘finesse.’”

So I present them with a 21st Century piece written by a conductor who is trying to somehow pay his musical dues to the orchestra by contributing a composition – since the only instrument I play well at all is the orchestra itself – and suddenly I want the strings to sound not as sober or sweet, but maybe a little drunk and brash.

In rehearsal of “Indication for Strings,” I admonished them to “punk it out,” and play what we all agreed was “dirty strings.”

Even in the current work we are rehearsing, “Emendation,” we need to come to terms with this shy sound and be done with it. The music needs more horsehair in it, with about 90 percent of the bow in play.

And attitude.

Presently, the sound is afraid of the notes. I would love to reverse this and make the notes afraid of the sound.

If my players were Olympian athletes, I would want all discus throwers. Rhythm, finesse, speed and strength meet, and the disc is hurled as far afield as possible. In this way, a mezzo-piano whole note should smack the back row between the eyes such that they momentarily live the sound.

I cannot lay blame for this on the players. In other, better music, especially Haydn and Mozart, I most frequently use the term “finesse” to evoke a joyfully measured forte. “Excitement, not anger,” I will say. “In Haydn, ‘f’ means ‘finesse.’”

So I present them with a 21st Century piece written by a conductor who is trying to somehow pay his musical dues to the orchestra by contributing a composition – since the only instrument I play well at all is the orchestra itself – and suddenly I want the strings to sound not as sober or sweet, but maybe a little drunk and brash.

In rehearsal of “Indication for Strings,” I admonished them to “punk it out,” and play what we all agreed was “dirty strings.”

Even in the current work we are rehearsing, “Emendation,” we need to come to terms with this shy sound and be done with it. The music needs more horsehair in it, with about 90 percent of the bow in play.

And attitude.

Presently, the sound is afraid of the notes. I would love to reverse this and make the notes afraid of the sound.

If my players were Olympian athletes, I would want all discus throwers. Rhythm, finesse, speed and strength meet, and the disc is hurled as far afield as possible. In this way, a mezzo-piano whole note should smack the back row between the eyes such that they momentarily live the sound.

Monday, March 29, 2010

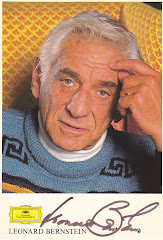

The Sheridan paragraph from Leonard Bernstein's biography

"On their roundabout way home from Taos the Bernstein brothers visited Gus Rudolph, a Tanglewood student, at his ranch in Sheridan, Wyoming ... 'We plunged into the strenuous Wyoming life, working in effect as hired ranch hands from dawn to dusk and then drinking beer in town at night with the local cowboys.' Bernstein used a snapshot of himself on horseback as his 1949 holiday greetings card." (Page 182, Leonard Bernstein, by Humphrey Burton)

He had with him the uncompleted score of his second symphony, "Age of Anxiety," with which he was tinkering while on the road.

Bernstein, his brother and poet Stephen Spender drove here in Lenny's Buick convertible.

He had with him the uncompleted score of his second symphony, "Age of Anxiety," with which he was tinkering while on the road.

Bernstein, his brother and poet Stephen Spender drove here in Lenny's Buick convertible.

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Piano Audio Recordings Not For Me

I studied for a time with Canadian Composer David McIntyre, a student of Aaron Copland, and who subsequently introduced me to Lukas Foss and Gregory Millar. (Hey, if can't drop names in your own blog you wind up doing it indelicately in forced conversation).

I was auditioning for a collegiate choir in Canada where David was teacher and accompanist/arranger/composer. Without knowing he was brilliant -- plus the fact that he looked to be about 12 at the time -- I plopped my score from Bernstein's "Simple Song" from the Mass onto David's piano in prepartion to belt out the baritone.

"Oh, Bernstein," David said.

"Yeah," I said. "Think you can handle it?"

What a fool I made of me!

David taught me the value of placing myself under the more direct influence of music. He was an encouraging, quiet and profound musical presence in my life in those days.

Therefore, I have to say, I have avoided piano audio recordings like the plague. It is much so much more exciting and immediate to sit in the same room, in close promximity to the artist -- with nothing but our humanity and the inate spirituality that chaperone's all music into one's soul between us. This is electric and personal. It is important for me to see the artist's movements in the playing and performing. The artist and the piano become singular as the player becomes more essentially musical, and the instrument accomodating and welcoming to the personal. The result is not merely music, but an experience in musicality.

Better to be in the concert hall, if not actually on the stage with the performer, as I accidentally was back in 1976 when Igor Kipnis performed on his harpsichord in the Fine Arts Center at the University of Wyoming during its Elizabethan Days. By chance, myself and some of my motley friends were seated on overflow chairs on the stage. I was arm's length from the tip of his right shoulder. The recording would have induced irresistible napping, but on stage with Igor was captivating.

I have just heard an afternoon of Chopin performed at the WYO Theater, but, I would no more buy the CD than I would purchase an audio recording of a Broadway play. The motion and contribution of the key ingredient is absent -- the musician.

Now, the DVD is another matter. CD, borning. There is just too much missing. It is like eating a photograph of a good steak.

I was auditioning for a collegiate choir in Canada where David was teacher and accompanist/arranger/composer. Without knowing he was brilliant -- plus the fact that he looked to be about 12 at the time -- I plopped my score from Bernstein's "Simple Song" from the Mass onto David's piano in prepartion to belt out the baritone.

"Oh, Bernstein," David said.

"Yeah," I said. "Think you can handle it?"

What a fool I made of me!

David taught me the value of placing myself under the more direct influence of music. He was an encouraging, quiet and profound musical presence in my life in those days.

Therefore, I have to say, I have avoided piano audio recordings like the plague. It is much so much more exciting and immediate to sit in the same room, in close promximity to the artist -- with nothing but our humanity and the inate spirituality that chaperone's all music into one's soul between us. This is electric and personal. It is important for me to see the artist's movements in the playing and performing. The artist and the piano become singular as the player becomes more essentially musical, and the instrument accomodating and welcoming to the personal. The result is not merely music, but an experience in musicality.

Better to be in the concert hall, if not actually on the stage with the performer, as I accidentally was back in 1976 when Igor Kipnis performed on his harpsichord in the Fine Arts Center at the University of Wyoming during its Elizabethan Days. By chance, myself and some of my motley friends were seated on overflow chairs on the stage. I was arm's length from the tip of his right shoulder. The recording would have induced irresistible napping, but on stage with Igor was captivating.

I have just heard an afternoon of Chopin performed at the WYO Theater, but, I would no more buy the CD than I would purchase an audio recording of a Broadway play. The motion and contribution of the key ingredient is absent -- the musician.

Now, the DVD is another matter. CD, borning. There is just too much missing. It is like eating a photograph of a good steak.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)